Chinese Fonts

历史 History

Click on any word to see more details.

From historical investigation, Chinese characters have an approximately 5,000 year history [Han Jianting 2008]. Rock paintings and patterns on clay pottery date back to the Neolithic Age in China and it may be that these are the origin of Chinese characters, becoming stylized and more abstract over time. One of the very earliest Chinese writing discovered, called Oracle bone script 甲骨文, was written on bone and turtle shell for the purpose fortune telling. These date back to about 1,300 BCE. A similar form of writing called bronze script 金文 was used on swords and other metal objects some time later. Chinese characters appeared later than Sumerian Cuniform and Egyptian hieroglyphs but Chinese is the oldest written language still in use today.

陶器 Pottery

Geometric symbols on pottery somewhat resembling later Chinese characters have been discovered at sites of the Dawenkou Culture 大汶口文化 (4,100 BC—2,600 BCE) in modern day Shandong province. Pottery markings were also discovered at the Bronze Age Erlitou Culture 二里头文化 (2000 BCE — 1500 BCE) site in Henan believed to be the the remains of the Xia Dynasty. The symbols at Erlitou resemble Oracle bone script 甲骨文 from the Shang and Zhou dynasties. The meanings of these pottery markings are not known but they may have either represented simple objects or names of clans.

Typical patterns in Shang Dynasty (16th—11th centuries BCE) pottery are shown in the picture below.

Different patterns have been found and classified by archaeologists, including animal mask 兽面纹, bird desgins 凤鸟纹, fire designs 火纹, lightening designs 雷纹, animal designs 动物纹, and dragon design 龙纹. The dragon design, shown below, and the fire designs resemble the modern characters 龙 / 龍 and 火.

甲骨文 Oracle Bone Script

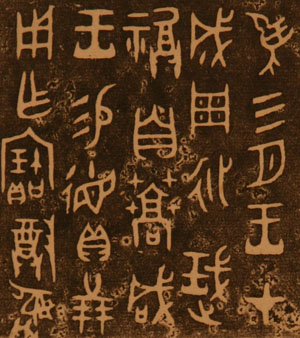

Oracle bone script or Jiaguwen 甲骨文 is formed from inscriptions on bones and tortoise shells from the Shang Dyansty (c. 1,700—1,045 BCE). They are often associated with worship of gods and ghosts but were also used for other, more general purposes as well. They were rediscovered in 1899 by Qing scholar Wang Yirong mixed up with Chinese medicine. They had come from Anyang in Henan province. This was the Yinxu site of the ruins of the Shang Dynasty capital. Today, over 150,000 fragments of Oracle bone inscriptions have been found at the site. 4,500 different characters have been found and, of those, more than 1,500 have been interpreted. The characters had very straight and thin lines, reflecting the method of inscription, which was carving with a knife. Tortoises are important in Chinese legends and that may explain the prefernce for using tortoise shells. Oracle script formed a relatively complete writing system. Divinations could include people's names, places, reasons, results, and verification of the divination Oracle bone script continued to be used in the Western Zhou (c. 1,045—771 BCE). Oracle bone script is the most important source of historic information about the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties.

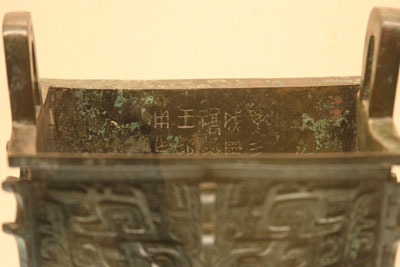

金文 Bronze Script

China entered the Bronze Age in about 3,000 BCE, approximately 500 years after Southwest Asia (the Fertile Crescent). Bronzeware in China during the Shang and Zhou dynasties was a high form of art. A script called Jinwen or Bronze Script was developed for use in bronzeware. In particular, tripod cauldrons (ding) and bells were known for their inscriptions. The cauldrons were used more frequently for ceremonies than practical uses and often had text recording important events. The bronzeware artifacts were important possessions and often buried with important people. Bronze script is similar to oracle bone script but simplified and written more neatly. This reflects the tools used to write the script: a brush was used to draw the character and then they were inscribed into the bronze. More than 3,000 Jinwen characters have been found and more than 2,000 have been decoded. The longest inscription of the Western Zhou is 497 characters on the Maogong cauldron.

小篆 Lesser Seal Script

Lesser seal script, small seal, or Xiaozhuan was the official script of the Qin Dynasty (221—206 BCE) defined in the period of standardization of characters. This was the first large scale standardization of Chinese characters, which unified the different variant forms that had emerged during the Warring States Period (475—221 BCE). The other forms during the Warring States Period are collectively called large seal script 大篆. The style was futher simplified from large seal script and became more rounded. More characters indicating sound and pictophonetic (including both a pictographic meaning and a sound) emerged. At this stage the pictographic meanings had mostly been abstracted to the point were it required a large amount of interpretation to deduce the meaning of the pictographic elements. All imperial inscriptions during this dynasty and frequently in later dynasties were written in lesser seal script. Lesser seal script has been used until modern times for offical seals and stamps.

隶书 Clerical Script

In the Qin Dyansty writing began to be used on a large scale. Officials in lower levels of Qin court used bamboo and wood strips to record events and other texts. The style that they used in writing quickly on the bamboo and wood strips was simplified and different in form from lesser seal that came to be known as clerical or official script 隶书. In order to draw the characters more quickly many of the curves in lesser seal were changed to straight lines. Clerical script is very similar to the regular script of modern Chinese. This was a large jump from mainly pictographic characters with some abstractions to a character set that was highly abstracted and nearly unrecognizable from the original pictographs that they were originally derived from. Characters serving as components in other lesser seal script characters like 水 (water), 手 (hand), and 心 (heart) were simplified and became the radicals 氵、扌、and 忄 in modern Chinese.

Clerical script was further developed after the Qin Dynasty in the Han Dyansty. The style used in the Han is called Han Li 汉隶. About 30,000 bamboo and wood strips with clerical script were excavated from the Han Dynasty Juyan site alone. Paper was invented in the Western Han Dyansty (206 BCE—25 CE) but not widely used until the Eastern Han Dynasty (25&mdash220 CE).

楷书 Regular Script

The most common script in use today is regular script 楷书. It is easy to read and create printed fonts for. Regular script evolved near the end of the Han Dyansty from clerical script and matured in the Sui (581—618) and Tang (618—907) dynasties. Compared to clerical script it is more square and regular and the strokes are more straight than curved. The hook emerged as a characteristic of certain strokes.

Cursive script (grass script) 草书 is a free flowing form of handwriting, equivalent to cursive writing of Latin letters. Many calligraphic works in cursive script are highly valued but are very difficult to read. It is entirely based on regular script. However, some simplified variants of regular characters have been inspired from cursive script.

简化字 Simplified Characters

Chinese characters were simplified one by one periodically throughout Chinese history. However, a major initiative to simplify characters was carried out after the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 to address the problems with the low literacy rate in China at the time. The resulting set of characters differs from the traditional characters 繁体字 still in use in Hong Kong and Taiwan and in many Chinese language schools and departments outside China. Simplified characters were announced in 1964 in the Complete List of Simplified Characters 简化字总表 national standard and revised in 1986. There are a total of 2,235 simplified characters replacing 2,263 traditional characters.

In most cases there is an unambiguous relation between the traditional and the equivalent simplified character. However, there are some exceptions. For example, the simplified character 台 may be any of the traditional characters 台(台灣 Taiwan)、臺(平臺 channel)、檯(櫃檯 sales counter)、or 颱(颱風 taiphoon). There are only a handful of cases like this.

异体字 Variants

Amazingly, characters that were in use over 2,000 years ago are still part of the Chinese language today. Not surprisingly, however, some of the characters changed in form over the years. These are called variants. A variant is conceptually the same character, with the same meaning but is written differently. A variant of the character ming 明 used by Tang dynasty calligrapher Yan Zhenqing is shown above.

In some cases a character was written a very different way in the past. For example, this is the way that Yan Zhenqing wrote the character bing 并(traditional 並). The rendering looks more like the variant 竝.

Another example is the character wei 为 (traditional 爲), for which 為 is the more common form today. It is very stylized and does not match either form that well. The line between variant and style is not distinct.

The list of standard characters is given by the Commonly Used Characters in Modern Chinese [Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China 1988].

Republic of China 1988].日文 Japanese

Japanese characters originated in China beginning in the Tang. Japanese characters in many cases from Chinese characters because of the variants that have been retained, the calligraphic styles that have been standardized on, and the simplifications made. Japanese simplified characters are called shinjitai 新字体. The characters overlap but with many differences. Many of the variant characters in Japanese are obsolete or considered incorrect in Chinese although they can be understood. From the pronounciation of many words in Japanese it is apparent that the pronounciation as well as the written form was borrowed. Examples of characters that are similiar but different to Chinese characters are 発 (to send out), which is equivalent to the simplified Chinese character 发 and traditional 發.

For more on the history of Chinese characters see the book Chinese Characters [Han Jianting 2008].

Dictionary cache status: not loaded